The Cycles of Life in Exile

Bible Studies, Messages, Papers on the Book of Ecclesiastes

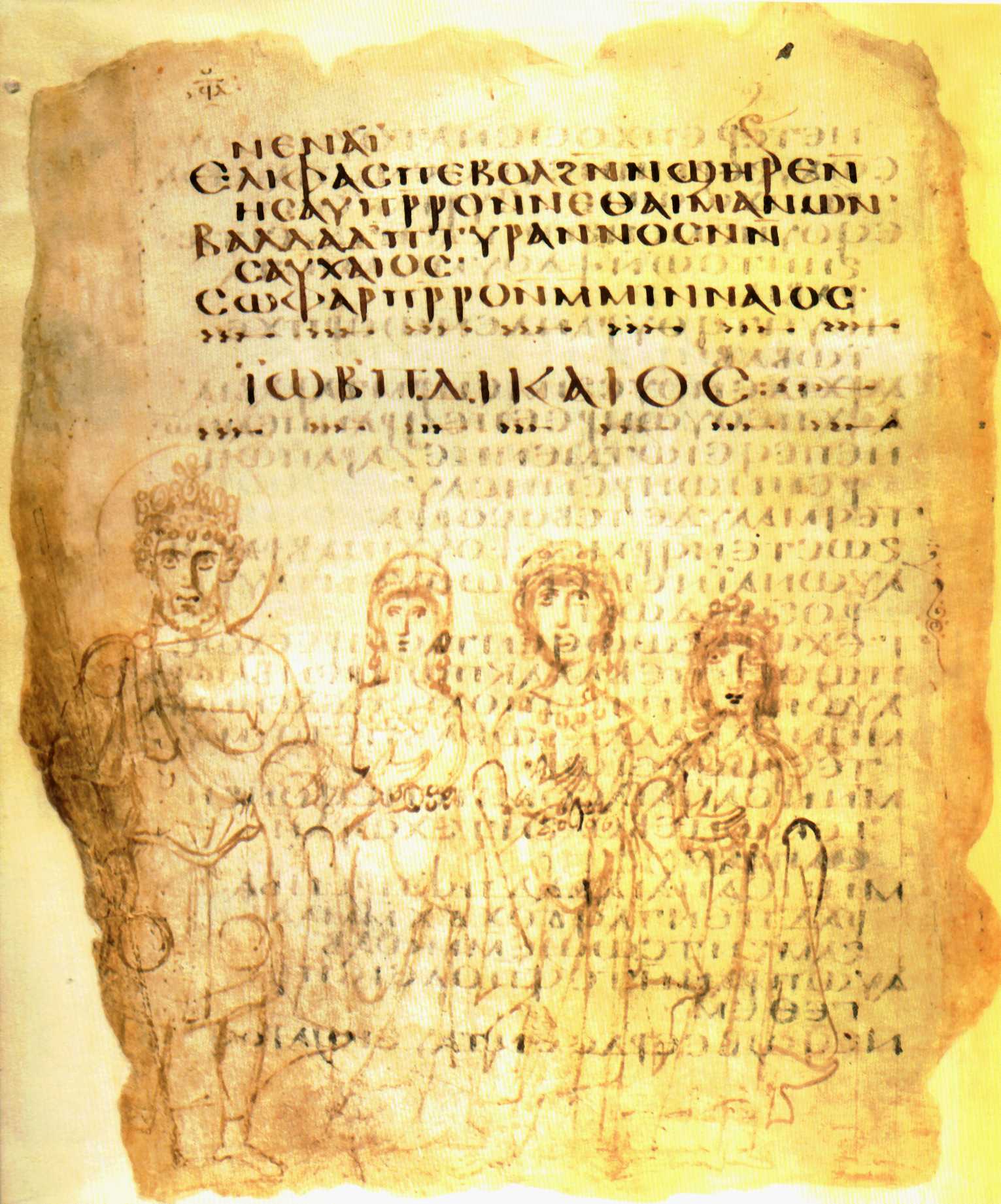

Photograph: This is a medieval European manuscript with an illustration of Solomon laying his father, King David, to rest. King Solomon is believed by tradition to be the author of the Book of Ecclesiastes. Photo credit: GoShow, Wikimedia Commons.

Below are messages, small group leader notes, and exegetical notes on the Book of Ecclesiastes.

Messages on Ecclesiastes

Ecclesiastes 1 - 2 The Search for Meaning in Circularity

Notes and Essays on Ecclesiastes

The Heir of David: A Thematic and Canonical Analysis of the Writings

Essay exploring how the Writings — the third group of the Hebrew Bible according to the Jewish tradition — are arranged. There is a garden-to-exile-to-restoration theme that can be discerned in the orderings of the books in the Writings. The Writings develop the readers’ hope in the Heir of David as the one who will bring about the restoration from exile, and return to the garden land.

Other Resources on Ecclesiastes

David Wolpe, Judaism at the Crossroads, Again. Dispatch Faith | The Dispatch, Jul 6, 2025.

The sub rosa religion of progressive Jews before October 7 was epitomized in the ubiquitous Jewish phrase tikkun olam—the concept of repairing an imperfect world. It has a long history. In Ecclesiastes 1:15, the world is called a twisted thing that cannot be made straight or repaired (the Hebrew is litkon, from the same root as tikkun). Already we have a sense of the despair that the term will later be intended to allay, presaging Immanuel Kant’s famous declaration that from the crooked timber of humanity, nothing straight can be made.

Kant might aptly have commented on the crooked timber of tikkun itself. The growth of tikkun olam into a concept started with the Talmud and expanded in the Kabbalah. The Talmud discusses the concept of “for the sake of repairing the world” in the tractate concerning laws of divorce (Mishna Gittin 4:2), and it is tied as well to other social legislation. In the Kabbalah, particularly in the hands of the mystic R. Isaac Luria, tikkun becomes repair for the catastrophe of shevirat hakelim, the breaking of the vessels, that occurred at the outset of creation. Certain meditations, prayers, and observance of the mitzvot (commandments) will bring repair, not only in the material world but also in God’s own self—a daring idea that has made Kabbalah both attractive and anathematized. Tikkun thus developed from a social concept to a supernatural one, and there it rested until the modern age when it returned to social dynamics with a vengeance. To quote the French poet Charles Péguy, “everything begins in mysticism and ends in politics.”